Jesus in First Century Judea: politics and Masculinity

Prof Helen Bond is Professor of Christian Origins at the University of Edinburgh, and Director of the Centre for the Study of Christian Origins. She has written books that are full of insights for people putting on Passion Plays and they include Women Remembered: Jesus’s Female Disciples, The First Biography of Jesus: Genre and Meaning in Mark’s Gospel, and The Historical Jesus: A Guide for the Perplexed. Her research focuses on the social and political history of first century Judaea, the historical Jesus and the canonical gospels.

You can listen to her lecture titled ‘Did Jesus have female disciples?’ here.

Prof Bond’s Quotes

“The historical Jesus is the real historical man who stands at the basis of this faith, whilst the Christ of faith is Jesus as he has become over 2,000 years of Christian speculation.”

“The more you know about the Gospels, the more you realise that they’re poetic, they’re imaginative, they’re trying to show you the truth about Jesus through creative ways that don’t always map onto what would have been recorded by a video camera.”

“Ancient biographies were quite unlike modern-day biographies. They were really about holding up a great figure as an example of a way of life that the audience might want to follow…And in biographies, although there is often a broad interest in getting the facts more or less correct, they often play fast and loose with historical material.”

“For an ancient person, it’s just not a question they’re going to ask—’Did that happen? And if it didn’t happen, am I going to be suspicious?’”

Prof Bond provided notes for the Edinburgh Passion Play in 2025 on the political situation in first century Judea and you can read extracts below, with the full notes on the website of the Edinburgh Easter Play.

The Political Situation in First Century Judea

At the time of Jesus, the small territory of Judea was under direct Roman rule, with a governor (such as Pontius Pilate) in charge. Much of the day-to-day running of the country was left in the hands of the traditional Jewish leaders, the priestly aristocracy in Jerusalem. But these men always had to operate under the beady eye of Rome – one wrong turn and they could lose their position. The Roman governor came to Jerusalem a few times a year to see what was going on, bringing with him a number of auxiliary troops. Not surprisingly, tensions were always high during these visits, and riots and upheaval were common. As the capital city, Jerusalem was rich and cosmopolitan. Although Jewish, it had been heavily influenced by both Greek and Roman culture, and Jerusalem’s elite shared the same ideas and outlook as elites in any other city. At the centre of everything was the Temple, where sacrifice was offered to the Jewish God. The whole complex had been lavishly refurbished by Herod the Great, turning it into one of the wonders of the ancient world. At Passover, the city was full to bursting with pilgrims and tourists and tensions were high.

How to be a man in the ancient world

Like other societies at the time, Judea was thoroughly patriarchal. The fundamental unit of society was the household, and the male head had a great deal of power over his family (and slaves, too, if he had them). Legally, politically, and economically, men were in charge. But it wasn’t enough just to have all the power, it was important that others held you in honour and respect, that you were seen to be “manly.” (The opposite was to be shamed, humiliated, or to be a laughing stock.) Men could become manly in a number of different ways. Coming from a good family automatically gave you a certain respect and standing, as did wealth. But the best way to assert your manliness was through glory won on the battlefield, through a display of courage, endurance, quick wit, and prowess with the sword. Even if you weren’t victorious, a noble death for your country established an enviable legacy as a manly man.

Not everyone was cut out for warfare, of course, and there were other things you could do to enhance your manliness. A man skilled in oratory, who got the better of others in debate, would also be seen as a good male role model, as would a just father at the head of a well-ordered household. A “true man” was expected to show moderation and restraint, not to become too emotional or passionate about things. But he was very much an alpha male – active rather than passive, striving to be first at the expense of others, ready to dominate others (especially women and his social inferiors).

Jesus’ central teaching is that the first should be last, and that people shouldn’t strive for glory and power. If anyone wants to be his disciple, he says, they should be willing to be last of all, to be like a slave (see Mark Chapter 8). What Jesus is describing here is, in many ways, the kind of behaviour associated with women, who were also expected to be passive, not to take the lead, and (in most homes) to serve others. In effect, Jesus says to his followers that they should strive to be more like women in character than alpha males.

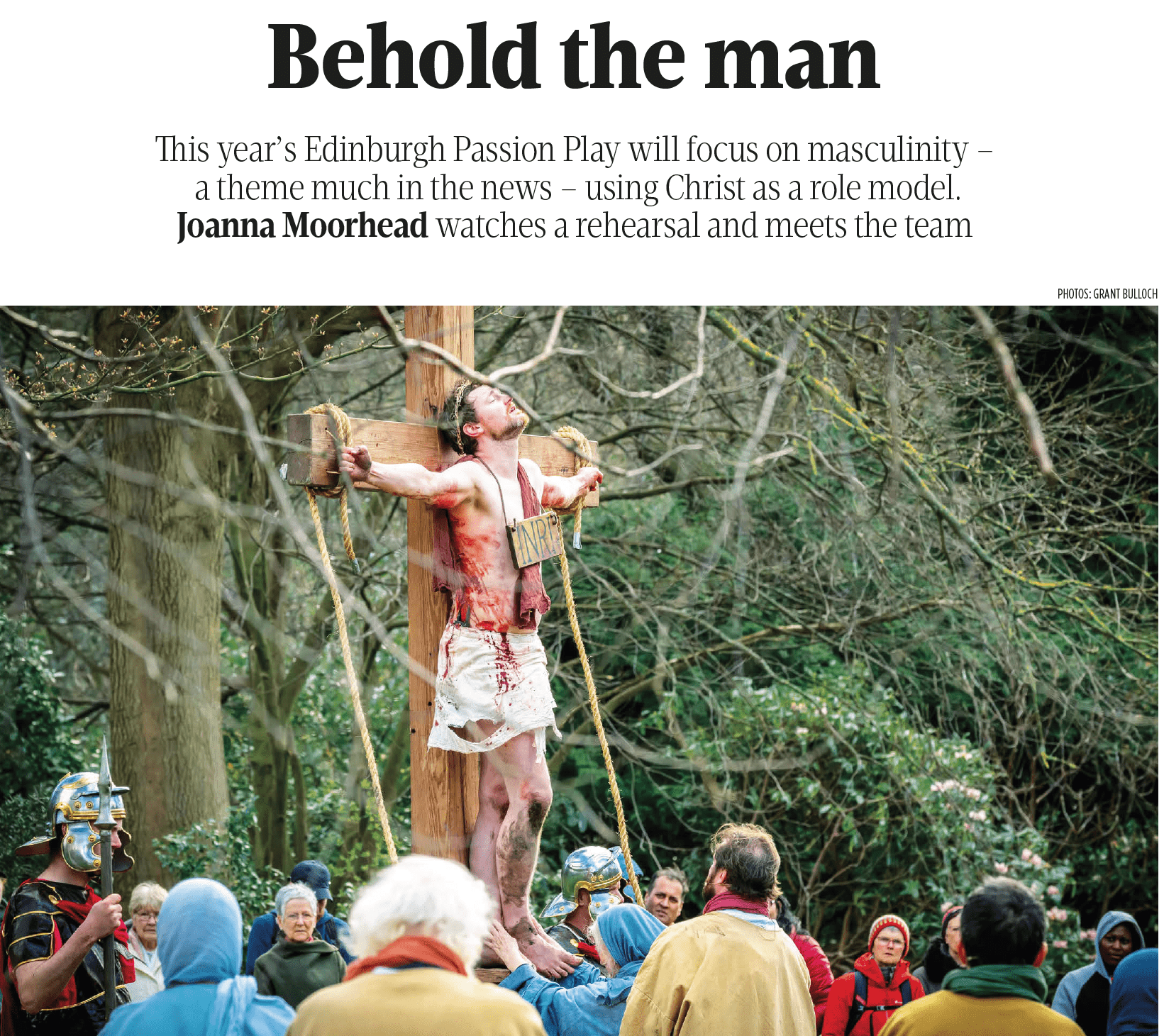

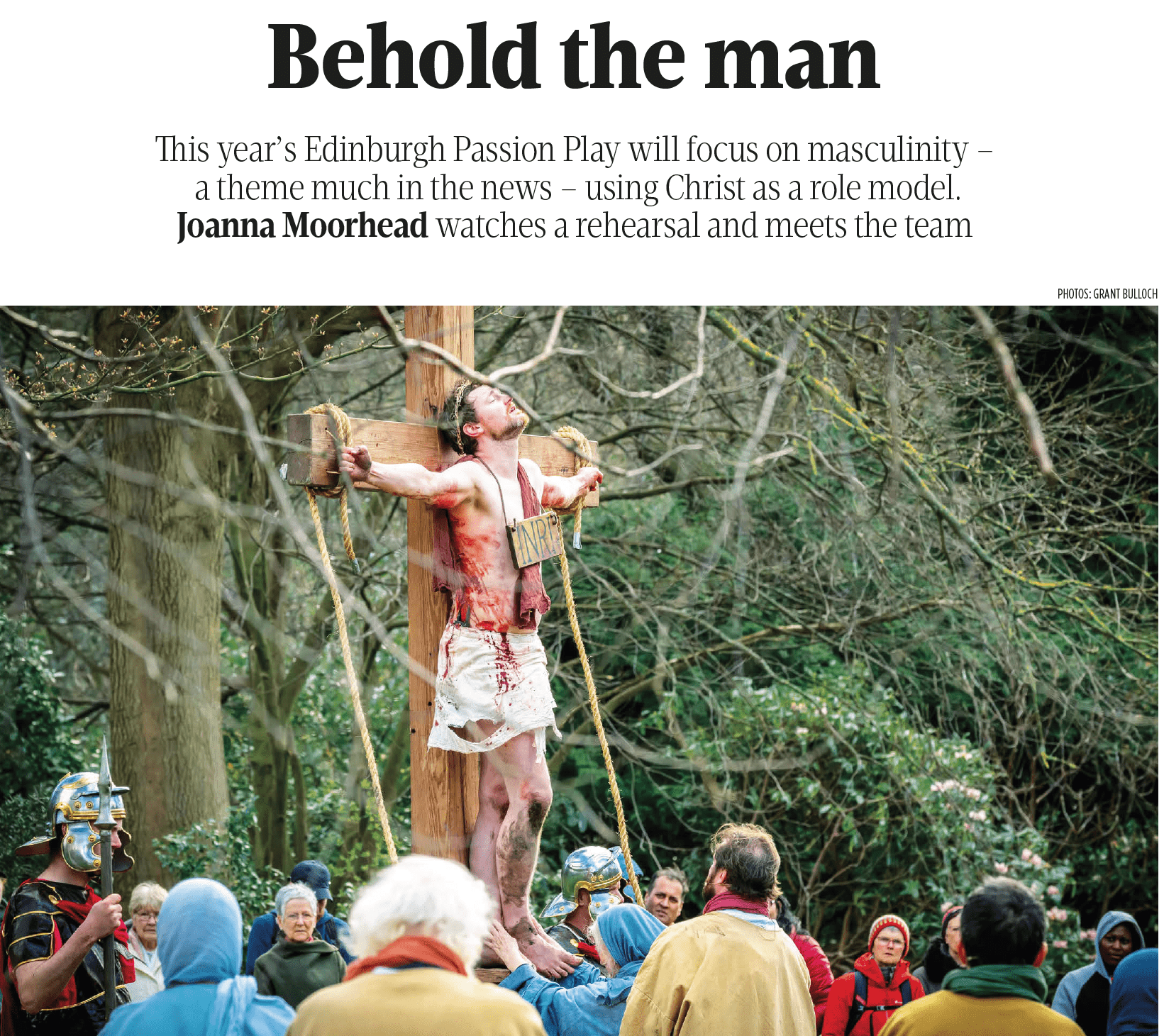

Another place where Jesus loses his manliness is at the cross. Crucifixion was a slave’s death, reserved for bandits and nobodies. Throughout this part of the Gospel story, Jesus becomes entirely passive as other people do things to him. He’s handed over, nailed to a cross, and made fun of by a whole range of people. In the eyes of the world, he’s entirely humiliated and shamed. Of

course, the Christian claim is that it’s precisely in this shame and lack of manliness that true honour is found. The Christian message turned much-received wisdom on its head, reaching out to the poor and marginalised and urging followers to seek honour in service, manliness in putting others first.

Further Research

Here’s a link to Colleen Conway’s book, Behold the Man: Jesus and Greco- Roman Masculinity (Oxford University Press, 2008)”

https://www.bethanyipcmm.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Conway-Behold-the-Man-Jesus-and-Greco-Roman-Masculinity-2008.pdf

And a link to an (extensive) preview of Stephen D. Moore and Janice Capel Anderson’s New Testament Masculinities (Society of Biblical Literature, 2003): https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/New_Testament_Masculinities/Mys52UiCZYYC?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA2&printsec=frontcover

If you are interested in the history of Bible times, you can listen to more of Prof Bond’s research on her podcast titled Biblical Time Machine Podcast (Listen on Apple Podcasts) https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/biblical-time-machine/id1648738323

(Listen on Spotify) https://open.spotify.com/show/7cNljZzhe4w3zL9t0MaOZH?